[Prologue. Many people are victims of phobias. I am also their prey. The most acute one, is the phobia of needles and, consequently, syringes. This phobia makes my hands sweat even in these moments as I type on the computer keyboard. The cause of this phobia is very clear to me and I have understood it in time. It has to do with my childhood, in Tirana, in the early 1980s, when I was about four or five years old. At that time, my grandmother, when she decided to let me go out and play alone outside, in order not to let me go too far from the building where I lived, she would say to me: “Do not leave or else arixhofka will grab you, put you in a cauldron with needles and take your blood! “. When I asked her what an arixhofka was, she told me that she was a black old woman, the colour of which I interpreted more as a result of lack of hygiene than as having any racial connotation. So I imagined that black old woman as a dirty person, who did not wash often. Moreover, because my grandmother had explained to me that the arixhofka took its name from the bear, which she carried with a rope tied behind a ring that she had inserted into its nose, I also imagined her as a wanderer, dressed in rags, running around from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, as if to have fun, but actually to kidnap small children.]

The first Albanian feature film was Fëmijët e saj – (Her Children), 1957[1], directed and written by Hysen Hakan, who premiered it as his graduating work in Czechoslovakia where he studied at the time. The short film has entered the history of cinematography as the first artistic production of Kinostudio “Shqipëria e re” (The New Albania), founded in 1952. Being an industrial production of Kinostudio, Fëmijët e saj, as a film, implies in a Lacanian way, that parole (aspect of artistic individuality, the author’s voice), belongs artistically to langue / the language of the cinematography of socialist realism, the only langue artistic method allowed in the Socialist Popular Republic of Albania, since 1953, when it was approved by Albania’s League of Writers and Artists, until the change of the political system, in 1991.

In addition to the influence of authorial discourse (parole) through the language (langue) of political power, the theme of the film — vaccination-immunisation of Albanians to resist infectious diseases — was not the fruit of Hysen Hakani’s creativity, but an instrumental part of the programme. To sensitise people towards government campaigns, the Albanian Labour Party aimed for the good health of the New Socialist Man. While, as a genuine artistic interpretation of the author, it can be called the dramatic idea of the film, or story concept: Fatimja (Marije Logoreci), lives in a mountain village with her young son, Petrit (Xhemal Berisha). He dies, infected by the bite of a rabid dog, because his mother, instead of sending him to the hospital, as suggested by the village teacher (Naim Frashëri), had sent him, on the advice of a religious villager, Beqir (Loro Kovaçi), to a witch or folk doctor, Hall Remja (sic) (Bejtulla Turkeshi).

From the narrative point of view, the script in this work of Hysen Hakan, has a classical division into three acts — beginning, development, conclusion/exposition, climax, denouement (Poetics, Aristotle) — where the psychological development of the character of Mother Fatime is at the very centre.

Act One: The photography, in the first photograms of the film, frames — in an extreme long shot — a pastoral, mountainous landscape, with a few simple wooden houses. A cry is the connecting bridge through which the director chooses to lead the spectator, escorting them from the classic, romantic background to the second frame — medium long shot — where this time the frame captures an almost crawling child being pulled hard by a woman. Further, outside the film’s objective diegesis, a laugh precedes and connects the third frame, where, through a holistic shot — master shot — to complete the first scene of the film, in addition to the woman and the child — who persists in his resistance — enters a man in a suit and another woman in a nurse’s uniform, holding several ampoules for injections in her hand.

The voice (the cry of a child and the laughter of an adult), mounted in a choral form with the gradual shots chosen by the author, communicates to the spectator the dramatic range of the event.The text begins “Kadri, do not shame your mother!” uttered by one we soon understand to be the village teacher, then the “mother” replies, “No comrade teacher, Kadri will honour me!”. So from the beginning, we have an educational (via the teacher) and health/sanitary (via the nurse) message enforced on the resistant-child subject. This message is conveyed to the child through psychological pressure, exerted by adults, through the two main keywords of Albanian traditional and canonical culture: shame, towards the other (teacher, nurse), and family honour (mother).

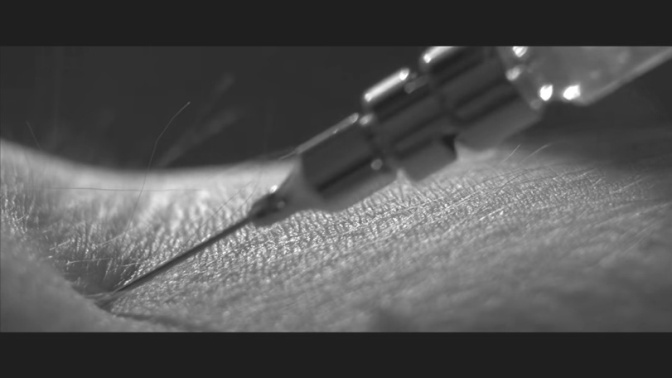

Meanwhile the nurse fills the syringe (Hakani uses a detail shot, or insert, the opposite pole of which, in the history of world cinema, can be seen in an extreme version in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction).

Kadri, already calmed down, is injected with the vaccine.

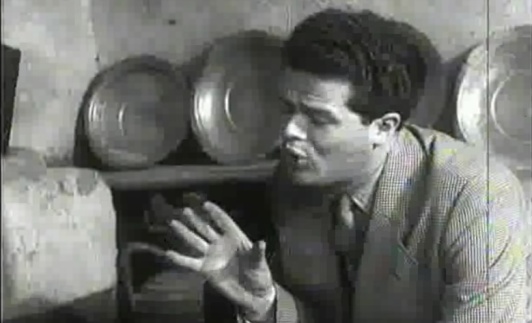

The nurse then asks the “mother” if the young child is her son. “No, I have no children!” she answers, shocked. The nurse waits for the child and woman to leave then asks the teacher why the woman is shocked. Then the teacher (symbol of the emancipatory knowledge of scientific socialism and historical materialism) begins to tell the “ancient” occurrence of Fatima, paving the way for flashback (at the end of the film the spectator learns that the time frame of this flashback is 13 years , i.e. the year 1944, the month of August, before the liberation of Albania and the installation of state socialism).

It is important to note the choice of the words of the director-screenwriter. After the phrase “ancient occurrence” – and not “old occurrence”, as would be the correct linguistic form for narrating an event involving a living person (mother / Fatime) – we have an attempt by the author to expand and exaggerate the semantic field of the film narrative. This is demonstrated by the not at all accidental use of the superlative habit in question, which is emphasized through the diction of Naim Frashëri (unnatural pause between the words “ancient” and “occurrence”) and even more pronounced by the character interpreted the teacher, presumably the one with a rich and confident Albanian language vocabulary. Thus, through this strategy, the semantic field of the film narrative expands, which, through Fatima’s personal tragedy, opens the way to the metaphorical, symbolic and paradigmatic reading of ‘the backward’ Albanian context along its past, shortly before state socialism or distant to the end of time. After all, the author’s aim is to highlight the past – whether the recent one 13 years ago, or the distant, “ancient” one and to emphasise its contrast with the new socialist world made into a reality.

Act Two. The “ancient occurrence” which the teacher indicates, opens up, with an unusual setting,- “the village seemed desolate.” This setting contrasts with the bucolic image of the mountain village amidst a diverse flora. Thus, after we see a child (almost a baby) being fed by (probably) his sister (their clothes are poor, just like the house in the background) while the mother is filling water in the well (we can easily conclude that the water flowing inside the house does not exist), we understand that the desolation reins in the life of the villagers and not the village itself.

A woman’s scream is immediately heard in the background giving the alarm: “Rabid dog! Rabid dog! “, are her words. With a load of wood on her back, which confirms the desolate condition of the villagers, the woman who is giving the alarm, passes in front of the house of the characters we just saw, running and terrified. Instantly, the mother of the children releases the winch and the bucket of water falls out of the well again. She runs towards the children and pulls them towards the house. The older girl remembers the plate of food left in the square and returns to pick it up. Her mother follows her and pulls her back towards the house without letting her reach for the food plate. Hence, we understand that, the risk of viral infection, as a result of the bite of the “rabid dog”, for the villagers of “ancient” times was more of a priority than any job (mother leaves the job of filling water), even more important than food.

[Intermezzo. At this point, it is time to open up a parenthesis with the actuality of Hysen Hakani’s film. So, as the author presents the events, every “ancient” villager knew how to isolate themselves in voluntary lockdown, without the need for coercive (schedule) and threatening (fine, prison) measures of the Nazi government of the time (recall that the event is August of ’44). Thus, the comparison with the actuality of the COVID19 pandemic, with us, as hyper-technological and super informed citizens, and our contemporary democratic governments, is much needed and useful. The simple conclusions of this comparison can be drawn by anyone, but the purpose of this text is to highlight the complete erasure of concrete cultural knowledge or knowledge about the things of the life (viruses, for example) of “ancient” peasants and our ignorance towards them.]

As stated, the rabid dog fatally bites Petrit, Fatime’s son, who sends him to Hall Remja for treatment. From the semantic point of view of the Eisenstein style of editing found in Hakani’s images [2], it is important to note that, the syringe detail (mentioned above), as a solution to the viral infection problem, rhymes with the dog’s mouth detail (Detail Shot), a direct agent of the virus transmission material. Also the same image rhymes with the detail of the plate that releases magic vapors in the hands of Hall Remja (Detail Shot), the indirect, immaterial agent of virus transmission. These are the only details (Detail Shots) of the film, which constitute the semantic essence of his dramatic idea.

This second film by Hysen Hakani [3] also shows a kind of theatrical sensitivity of the author (characteristic of his films), which does not depend only on the participation of some of the most famous actors of the Popular Theater troupe, Naim Frashëri, Marije Logoreci , Pjetër Gjoka, etc. This theatrical sensitivity is also noticed in the transformation of the textual material. The most obvious example of the author is that (as seen from the images below) with the character of Petrit, who lies ill and, quenched by thirst, seeks to drink by uttering the words “water, water” (ujë, ujë in Albanian). Hakani, by working on the voice as sound and not just as text, conveys the irreversible transformation that the person affected by the rabies virus undergoes. Thus the pronunciation “uuuuuuj, uuuuuuj” of the words of the text transforms Fatime’s son almost into a small dog, which cries, adding pathos to the most painful scene of the film, Petrit’s death.

Act Three. Hakani actualizes the transition to the last act by overlapping a field-plan, where the full shot of Fatima kneeling and leaning face down on the day of her son’s death, recovers with her being between children jumping happily, 13 years later.

The text of the second act closes with the cry of Fatime’s lament “My Son!”, While in the third act, the teacher closes the text accompanied by the return from the flashback:

“That is what happened 13 years ago. Now, she [Fatima] works in our kindergarten. The children love her very much and call her mother. She loves them too, as if they were her children.”

The moral of the fable told by Hysen Hakani leaves no room for doubt: the only solution to get rid of viruses is science, implied not only through its results (antiviral vaccines), but also as an approach against the backwardness of people’s folk superstitions. And science for Hakani was that of scientific socialism propagated as the emancipatory agent of the people by “Kinostudio Shqipëria e Re” and the art of socialist realism.

[Epilogue. This text is written in the framework of an invitation extended to me by the friends at the Lumbardhi Foundation of Prizren, to be included in the section of their blog Kinofigurimi. We previously agreed to go to a text on the retroactive purpose of cinema of the period of socialist realism (1953-1991), which interests me because I have long wanted to write something about the much debated current issue in Albanian public opinion, for decades now , the screening or not – due to the ideological and propaganda overload – of feature films of that period. My telegraphic answer to this question is what director Kristaq Dhamo said, almost a year ago, in 2019:

“Art is art. In every age, good or bad, it is a sign of history. And history must be respected. To be criticized, but to be respected. To ban movies, I think is an idiocy.” [4]

But, beyond the answer which is more than enough to close the useless discussion on the screening or not of the feature films of the Albanian socialist realism, two questions arise: What is the retroactive goal coming out of Hakani’s Fëmijët e saj? What is the purpose of the analysis of this film?

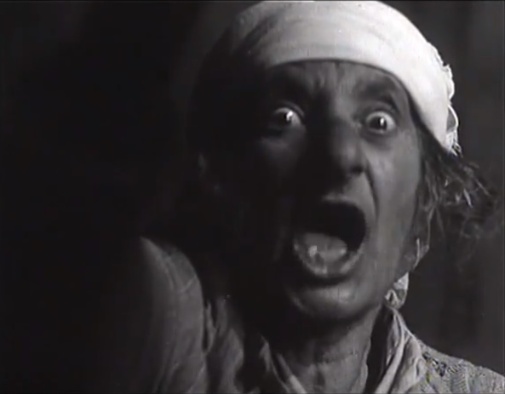

As far as Hakani is concerned, he leaves little room for the interpretation of the plot of this film: scientific socialism is the solution against the infectious viruses and folk superstitions of the people that, as intangible agents, transmit it. But something must also be noted that, if not evidenced, could pass as a complete condemnation of folklore and folk medicine by Hakani, which in my opinion is neither in the intentions of the author nor of state socialism. This is most evident in discrediting Hall Remja’s character within the script:

Fatima – Hello!

Hall Remja – Hello! What do you want?

Invitation – My boy was bitten by a rabid dog.

Hall Remja – What dog was it, red or black?

Fatima – For God’s sake, I do not know.

Hall Remja – Do not worry, I will cure the boy in seven days.

Moreover, the speculation on Hall Remja, preceding her text, is also shown by the director through the image, as in the case of the bag of food that a fleeing customer (Marika Kallamata) leaves in her hands, after she has provided the service.

And that the film’s approach is not intended to completely and dogmatically condemn folklore and folk medicine is also confirmed by Fatime’s recovery, which seems like a magical and triumphant miracle over her tragic past, materialized by children’s dance, which brings to mind not only the folk dances of the Albanian people, but also the dances of magical rituals. The latter could by no means be openly promoted in the art of socialist realism, and I do not believe they are conscious references by Hakani, but they can certainly be interpreted as part of his creative imagination. And it is the configuration and research of the creative imagination of the artists of socialist realism that this text also has as its main purpose.

P.S. : Conclusions … to avoid an ending. The period of state socialism and the dictatorship of the proletariat in Albania, consequently the art of socialist realism, are extremely complex and are often analyzed through the prejudices and clichés of public opinion, especially the contemporary mass media. And it is precisely due to this complexity that we must turn our eyes back, to the not-so-“ancient” history. For example, focusing only on today – when through the mass media bombing Albanians are subjected to lockdown or coercive measures not only voluntarily, but compulsorily, in a completely arbitrary way, unconstitutionally and illogically – what approach is needed towards medicine as a science and the folk medicine? What role do they both have and should they play in our lives? How much attention is paid to the speculative profits that arise not only with viruses, but also produce them? From this point of view, Fëmijët e saj, socialist realism, state socialism and the dictatorship of the proletariat, through their specific discourse, seem much more emancipated and emancipatory than what, in general, the discourse of contemporary politics and the scene of today’s Albanian art offers.

I want to close this article with an interpretive fugue of the last scene of the film Fëmijët e saj, which aims not to exhaust, but to further add to the complexity and the need to study the language of art and film (not only) of socialist realism and the questions that it resonates towards our contemporary actuality.

After the children’s dance that marks the magical miracle of triumph over Fatime’s tragic past, we see the latter in the closing scene leading a row of children following behind, imitating Fatime by opening their arms in the shape of wings and the flight of birds. As mentioned above, the director clearly works and opens the metaphor of the story of Fatime, a child of her children, as a sacred paradigm (like Saint Mary, daughter of her child, Christ) of Albanian history, rooted in culture, customs and the canonical tradition (shame in front of the other and the honor of the family / mother mentioned in the opening of the film). Thus, Fatime, after losing her biological child and realizing the mistake, is transformed, as the opposite pole of Hall Remja (halla- aunt, in Albanian, is the father’s sister), into the closest person, the symbolic mother, of all the children at the kindergarten where she works and, metaphorically, of all Albanian children. And it should be remembered that the symbol of Albanians is the eagle. But the opening of the wings and the flight of a bird with the little birds following it (Fatima and the children of the kindergarten) is more like a chicken coop, similar to a domestic and domesticated bird. Some questions arise: what can this tell us about the current situation of Albania and Albanians in the time of COVID19, about medicine as a science and folk medicine, about the obedience to the coercive and arbitrary measures of the government and the infantile treatment of Albanians, about the ethics of private benefits when public health is at stake? Of course, these are not questions addressed to us by Hysen Hakani of 1957, but by his artistic creativity, timeless, like that of any artist worthy of being called as such.

The original article was written in Albanian.

Romeo Kodra holds a Master in “Theory, Techniques and Management in the Arts and Entertainment” (Degree Category: Entertainment and Multimedia Productions) Faculty of Human Sciences, Bergamo University of Studies, Italy. He is an Invited Researcher at Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA – Paris) – Program Profession Culture 2016, International Affairs’ Department of Ministry of Culture and the “Lead Expert Evaluator” of “Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency” (EACEA) and “European Cooperation in Science & Technology” (COAST) of European Commission.

Romeo’s interests regard research on challenged spaces between the political power and arts in modern, transitional and contemporary societies as well as the polyphonic organization of spaces and artistic productions. This interest in practice is explored through video art, performance, theater, curatorial events, photography, writings on culture, art and critique of art.

Kodra lives and practices his activity between Tirana, Bergamo and Helsinki.

1] http://www.aqshf.gov.al/arkiva-1-1.html?movie=24 (link consulted on 26/12/2020).

[2] Hysen Hakani in a long television interview, broadcast in 2009, on the show “Histori me zhurmues” (Noisy History), mentions, in addition to Soviet films circulating as part of his academic training in Prague, the influence of Italian neorealism in his work, without giving details of where this influence consisted, except in the choice of location (the animal pantry of a Tirana house “where cows and chickens were heard”, but which are not part of the sound of the film and do not fully explain the influence of neorealism). Link consulted on 26/12/2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lXPNFoqU6Nc

[3] His first film is also a student work “Hotel Pokrok”, shot in Prague in 1956. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0314181/ link consulted on 28/12/2020.

[4] Link consulted on 28/12/2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HoTXfAiIv9w