The retrospective analysis of Žika Mitrović’s films, with the special emphasis on Captain Lleshi (1960), does not show a scholarly effort to prove its ‘artistic’ depth and neither does it present any feelings of nostalgia towards an idealised historical past. However, in an effort to capture its ideological underpinnings, rather an opportunity to treat this material from the perspective of it being historical documentation which would aim at a critical research of the political and social conjuncture, at a time when Kosova was excluded from a decent representation.

During the first two decades of socialist modernization, a very small number of films and documentaries were made in Kosova, compared to other Yugoslav countries. Out of 2977 productions (both fiction films and documentaries) that were made throughout the period of former Yugoslavia (1945-1966), only 32 films and 9 documentaries were made in Kosova. No local director contributed to their making and there are no films in the Albanian language from that time.

Unable to represent itself, Kosova was instead presented from the outside, through the imaginary of Mitrović, which Vehap Shita rightfully identifies in his assessment that “we have become recognised by the wider Yugoslav public and the world of cinema through the films of Žika Mitrović.” (Shita, 1962, p. 841)Therefore, the question that should be posed to start this analysis is: In what way does Captain Lleshi represent Kosova?

According to Vehap Shita, both of the Captain Lleshi films (Captain Lleshi and Gunfight) are artificially constructed, populated with untypical things, and misinformation. Moreover, he states that “Mitrović’s Captain Lleshi, especially in the second part of his cycle in Gunfight, has very little to do with who we are and is not created or imagined according to our perspectives and worldviews. ” (Shita, 1962, p. 841)

If the epic figure of Captain Lleshi does not represent the true face of Kosovo, as Shita says, then what was the main motivation for Mitrović to create such a film? Was Captain Lleshi a film commissioned for a particular political cause or was it just a good commercial opportunity, for financial gain and easy entertainment without having to worry about the consequences that such a representation might have carried?

In Albanian literature there are two different interpretive variants regarding the metaphorical messaging of the character of Captain Lleshi, and his ideological structure is constructed precisely on the basis of these two main components.

The first component is that which states that the film reveals a certain historical period and events that are generally considered as a sensitive and controversial topic within the Kosovar discourse. Consequently, it differs from other partisan films in that it does not show the fighting between the partisans and the Germans (except at the very beginning of the film)—as we are used to seeing in most partisan films—but focuses on the suggested local contradictions between the partisans themselves, namely Captain Leshi, and the ballistic gang led by Kosta, who count amongst their members, Ahmet, the brother of Captain Lleshi.

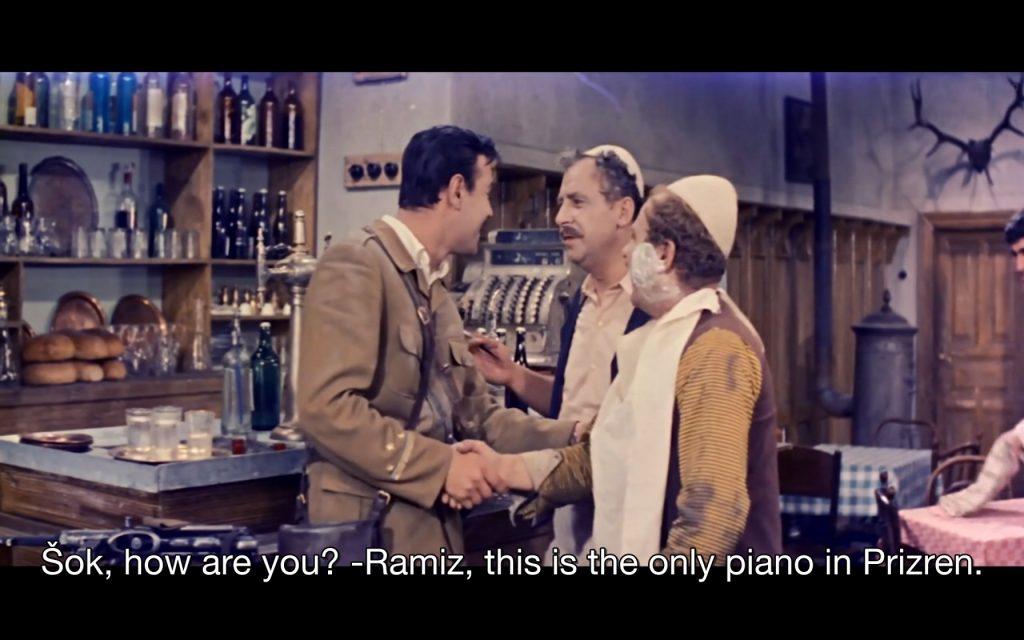

The second component is that which reveals that the whole cinematic adventure tries to be presented from a tacitly imaginary, or fantastical point of view. That Mitrović was not only satisfied in using the classic American Western style to reap success with his films, but that he also tried to incorporate ‘oriental’ visual elements (the spectacular clash between partisans and ballists at the Teqe of Saraçhana Helveti) and elements of ‘the exotic’ (the appearance of Albanians in traditional national costumes in the city tavern in Prizren), to stimulate in the public what is known as ‘the charm of the unfamiliar.’

Literary critic Vehap Shita is concerned with the second prong of these ideological forms, more precisely, in the cultural representation of Kosovo within these films. Here we are again, making reference to Shita, as it was he who made a cursory analysis of Mitrović’s films in his article ‘The Cycle Captain Lleshi and the Yugoslavian western’, published in the cultural-scientific journal Përparimi.

Shita claims that “while [in his]documentaries it seems to me that he followed a very good methodology [in his] presentation […], in the feature films thematizing our province, Žika Mitrović is more one-sided in terms of the motives or the treatment, and the genre he has chosen for their treatment.” (Shita, 1962, p. 837).

Finally, Shita emphasises that although Mitrović simply did not have even a basic understanding of the past or present, nor the psychology and mentality of the Kosovars, he does not consider “that his undertaking has bad intentions.” Shita insists that Mitrović was in a hurry when he completed the cycle of Captain Lleshi (especially Gunfight), and it was for this reason that he did not go deeper into the cultural heritage, in particular, the folklore and customs, and was instead informed only by things discussed here and there, and from reading sensational reports from certain journalists. (Shita, 1962, p. 840).

On the other hand, we also have the perspective of Arben Xhaferi, in the article ‘Captain Lleshi or Modeling of the Acceptable Albanian’, who insists that the realism of Captain Lleshi was not merely a commercial accident, but “an invention of the Yugoslav (Serbian) intelligence services of Ranković’s period, the Chief of the police and the security services of the country who [would] leave their posts in the IV Plenum of Brioni (1966).”

Moreover, Xhaferi emphasised that Captain Lleshi represents “a ‘positive’ model of the Yugoslavised Albanian; loyal and brave, who pursues, punishes, and liquidates Albanian ballists and nationalists that hindered their integration into the new system.”

In my opinion, both critical views of Captain Lleshi are one-sided and limited, because they concentrate only on one ideological component of the subject. Xhaferi tries to interpret Captain Lleshi from the political context, however his writing is permeated by a subjective and sensational momentum and indeed, a populist tone, full of preconceived categorisations, conjectures and assumptions, unable to argue them according to a theoretical-scientific methodology. Whereas Shita, although more objective, has a typically literary approach, focusing more on the description of the psychological motives of the characters and of the subject, but leaving aside the influence of the political and institutional circumstances of the country at the time.

Regardless of the fact that in Captain Lleshi, Mitrović tries to show the resistance in the partisan liberation war, we cannot say that it is a revolutionary film that shows the collective spirit of the partisans and a people’s mobilisation, but rather that it idealises and glorifies the superiority of the individual who is largely based upon the conventional standards of American Western commercial films.

In order to better understand the symbolic meaning of Captain Lleshi, we will take another critical journey, adapting Will Wright’s structuralist theoretical concepts in his important book Six Guns and Society: A Structural Study of the Western.

Will Wright has stated that the Western is a myth for contemporary American society. He challenges the theoretical views of Levi Strauss and other anthropologists, that primitive societies have myths while modern societies have history and literature. According to Wright, modern America has myths that resemble popular stories and the Western is one of them.

Making a detailed analysis of Western films, Wright comes to the conclusion that the mythical structure of the classical Western has three sets of main characters; the gunman, the homesteader and the rancher, who can then be interpreted in three mythical guises as the hero, the society, and the villain. These characters operate through an oppositional structure of identification: inside/outside, good/bad, strong /weak, wilderness/civilisation.

As we will see below, the opposition inside/outside presented by Wright cannot be said to fit perfectly onto the oppositional structure of Captain Lleshi. Nor is the wilderness/civilisation contrast applicable to Captain Lleshi’s narrative—although these two categories are similar, Wright maintains that they are not identical.

According to Wright, in contrast to the inside/outside dichotomy, society and the villain are internal units of differentiation aimed at prosperity, while the hero, arriving from the mountain symbolises the outside. In Captain Lleshi, even though the ballists identify with the perpetrators, they stay away. Even Captain Lleshi, who is considered a hero of the time, is not fully accepted in society due to rumours that his brother killed innocent civilians along with the other ballists. He also does not come from the village but rather from a rich family of beys.

Within the good / bad, the hero and society stand out as good, and the villain as bad. This identifying contradiction is partly applicable to Captain Lleshi. At first, he does not want to give the piano to the music teacher. This shows the dilemma and class conflicts between his traditional past and the altruistic role he is expected to assume in the new communist collective society.

In the strong/weak binary, the hero and the villain represent the strong whilst society is weak. Ballists and partisans in this instance represent the powerful while society is presented as a group that constantly needs protection.

Throughout the film, at no juncture does society appear in its collective form, except for a short moment, on the scene when through the loudspeakers we hear the news announcing that allegedly Ahmeti, Captain Lleshi’s brother, was executed by the state for treason. But even in that momentary image, the mass is not presented as an active subject, just a passive listener, everyone stays calm and no one reacts. This scene is in contrast to the last sequence of Isa Qosja’s film Keepers of the Fog (Rojet e Mjegullës). There, the collective scenes of the masses are shown from a distance, as well as the mobilisation of the masses as an active and conscious subject equipped and ready to fight political injustices as a precursor to change.

The final contrast of the oppositional identification is one of the most important ones present in Captain Lleshi. This is best achieved in its setting, in the city tavern in the centre of Prizren, in an effort to include all the different social, national and religious strata.

Here we find a strange scene that shows the image of a woman covered by a veil, sitting at a table, rocking a baby in the cradle among drunk men smoking and singing the most grandiloquent song in Captain Lleshi. We do not know if through this scene Mitrović wanted to present an Albanian, Turkish or Bosnian woman, nevertheless, the symbolism of the woman, with the veil and cradle, exhibits nothing but the long-standing, orientalist discourse that the problem with high birth rates in Kosovo lies in the practices of “religious backwardness”. I do not believe that Mitrović could be so careless as tomake this very well prepared scene, for the purposes of spectacle alone.

We have a black-haired tavern singer, Lola, who most likely serves to symbolise the Roma woman. I infer such, referring to the actress’ earlier role in the film The Roma Woman (Ciganka), and given the general Western template where singers, waitresses and entertainers are in most cases Indigenous Americans or Latin American. As a Roma woman, she represents a more disadvantaged societal stratum than the other woman featured in the film, the blonde teacher at the school of music, for example. While the teacher presents the prototype of a moral woman, Lola symbolises an empty-minded woman that Captain Lleshi may treat as a sexual object.

The only category that is missing in Mitrović’s imaginary social structural stratification are undoubtedly not the ballists, because they, like the others, identify with the feudal mindset. It is rather the music teacher who came from Belgrade to set up new cadres by teaching in Prizren. She symbolises the upper classes in the sense that she arrives from a civilised urban centre to educate and establish law and order in a ‘wild’ province like Kosovo. The educator from Belgrade is from the capital of a nation-state while all the others represent the categories of ‘nationality’, a term that has been among the most hotly contested topics Yugoslav literature—whether or the ‘nationalities’ are equally entitled to their citizenship. Captain Lleshi also tries to show the partisan war as a resistance born of urban areas, and not of the broader peasant masses.

In short, Mitrović’s Kosovo appears as a counter-productive place, forgotten by history, the tavern symbolises the only social institute, and that there is nothing but chatter and drunkenness in the city’s cafes for cultural activity.

What is also important in the structure of a classical Western is the functional dynamics of the structural narrative that develops in the plot. Wright identifies 16 functions of structural order:

1. The hero enters a social group.

2. The hero is unknown to the society.

3. The hero is revealed to have an exceptional ability.

4. The society recognises a difference between themselves and the hero; the hero is given a special status.

5. The society does not completely accept the hero.

6. There is a conflict of interest between the villains and the society.

7. The villains are stronger than the society; the society is weak.

8. There is a strong friendship or respect between the hero and a villain.

9. The villains threaten the society.

10. The hero avoids involvement in the conflict.

11. The villains endanger a friend of the hero.

12. The hero fights the villains.

13. The hero defeats the villain.

14. The society is safe.

15. The society accepts the hero.

16. The hero loses or gives up his special status. (Wright, p. 49).

Here we will not stop to analyse the development and functional structural order of the subject of Captain Leshi, but we will briefly address one of its functions, namely point 11. Although at first glance, it may seem that Captain Lleshi does not have a friend that the ballists could pose a threat to, it is the Captain’s brother who is endangered by them. As one scene shows, while Captain Lleshi looks at a photo of his youth with his brother, he enters into nostalgic memories and searches for the reason for Ahmeti’s involvement with the gang. As such, he makes no attempt to shatter the gang because it poses a threat to the society, but does so to save his brother. In this respect, the message of the film is reactionary because its action is driven by individual, biological kinship and familial bond rather than by any larger ideal that implies sacrifice in the name of a wider interest of the people.

Following the breakdown of Tito’s relationship with Stalin, Yugoslav cinema found itself in an unenviable position due to the cessation of financial aid. This caused the limitation of film productions and later provoked a reaction from artists and directors. With the ideological break-up from the USSR and the change of political course, Yugoslavia began to look to the West for an acceptable cinematic model that would be in line with official state goals. In contrast to European films that portrayed reality from a critical perspective, Yugoslavia turned to the entertainment model of American cinema. This cinematic style, in addition to attracting wide publics, was also useful in fortifying the ruling Yugoslav ideology.

The reorganisation of cinematographic policy, in parallel with the economic model of the socialist self-government, enabled the decentralisation of state cinematography in favour of small film houses to allow for free competition.

The system of market competition enabled the cinema houses to automatically violate the supervisory rules set by the state film commission.

Within this vacuum of cultural reforms, companies used the opportunity to invent more sensational and interesting script topics in order to attract as many spectators as possible. Undoubtedly, historical-nationalist themes were among them.

One such example of this trend are the films of Mitrović.

Mitrović has been criticised in Yugoslavia for the nationalist tendencies in two other films, such as those in Thunderous Mountains (Nevesinjska Pushka), which tells the story of a Serb-led uprising in 1875, against the Ottoman Empire, and The March on the Drina (Mars na Drinu), about the Battle of Cer against the Austrians during the First World War.

One of Wright’s central theses is that “the narrative structure must reflect the social relationship necessitated by the basic institutions within which they live. As the institutions change […], so the narrative of structure of the myth must change.” (Wright, p. 186)

As such, the film Captain Lleshi excels in reflecting the then economic and social institutions, as well as the hidden political tensions of the late 50s, as in most cases, the films made at the time talk more about the time when they were made than about the time they refer to.

[1] For more information on Kosovar cinematography, read the text by Petrit Imami ‘Film in Kosovo after the Second World War’ (Film u Kosovu Posle Drugog Svetskog Rata), and ‘The History of Cinematography and Television in Kosovo’ by Shukri Kaçanik.

[2]http://www.zemrashqiptare.net/news/15403/arben-xhaferri-kapiten-leshi-ose-modelimi-i-shqiptarit-te-pranueshem.html

[3] Will Wright, Six Guns and Society: A Structural Study of the Western (Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1975), 185.