The article we present below was written by Sezgin Boynik in 2007 and published in the Documentary and Short Film Festival, Dokufest’s official daily pages, doku daily.

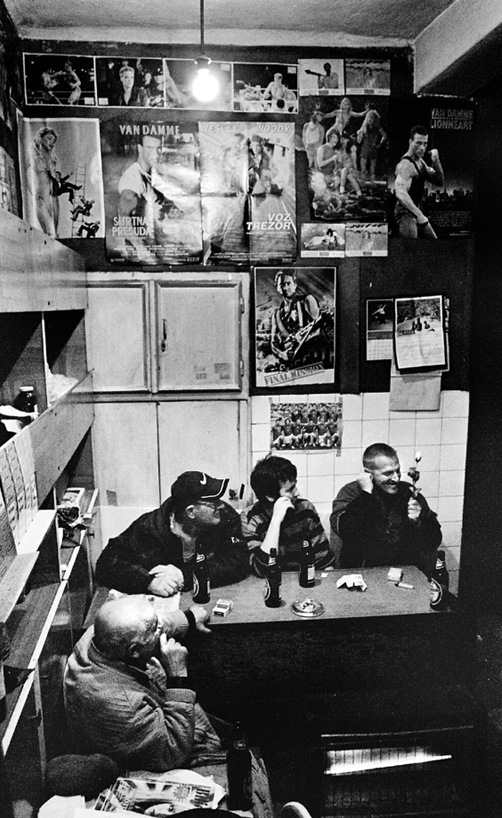

Sezgin depicts a curious period of Lumbardhi Cinema. The scene takes place in what is now known as the green room for meetings, which used to be a buffet, later turned into a café-bar where the carefully studied characters within the article — some of whom worked at the cinema — used to hang out every evening for many years until the property of the cinema became a contested site, with the intention that it would be turned into a parking lot.

More than just nostalgic writing, this is documentation of the heretofore invisible people, who took care of the cinema and were the living archives of decades of Lumbardhi’s internal, day-to-day operation. What Sezgin calls ‘the provincial modernism’ of this group of elderly men, to differentiate from a more classist approach, was in fact a group of outcasts in whom Sezgin and his friends found a mirror for how they perceived themselves in Prizren.

The derogatory term ‘qyli’ (the peasants, the villagers) used here to point out the savage attitude towards the cinema more so than to make a distinction from the ‘kasabali’ (the citizens, the civilized) is deeply ingrained in Prizren’s mentality, luckily vanishing slowly as a more nuanced understanding of both is coming to surface. The writing is filled with descriptions of local characters and characteristic elements which bring it closer to the literary genre of nonfiction. ‘Taksirat party’ is a rich document of a specific period of Lumbardhi that we are glad to have at hand in such vivid colors.

TAKSIRAT PARTY

Dedicated to Babo and Gjabir

This is a sociological and anthropological story about a very interesting community in Prizren, which will soon disappear. I will not narrate it in an academic way, since there is not space here to contain the specificities and peculiarities of the case. This is a story about people, all of them well beyond their 60s, who regularly gathered at the buffet of the Prizren cinema to discuss everything there was to discuss regarding Prizren, Kosovo, the wider world, and other things. I, along with my friends, first met them at Dokufest in 2004, having fun with their big, cheap, cold beers in Nikšićko bottles. These beers were the reason we quarrelled with some people, and were the reason we created and distributed a zine, Valdrin Prenkaj and I named “Fantazin”, which will forever be remembered as the little scandal of the festival, and as a very interesting experiment from the underground. But this is a different story.

Half a litre of cold, 50cent Nikšićko beer was reason enough for us to start bothering the elders of the cinema buffet. At the time, Montenegro was not yet an independent country, and the Nikšićko beer could not be found anywhere else. To put it in colloquial terms, at the time, Nikšićko beer was not considered a politically correct beer in other bars. We were intrigued, how this beer was here and who were these people drinking it? When we started going back to the cinema buffet, even after Dokufest, the only reason was to warm ourselves up before hitting the city and the nightclubs. But more and more, we started thinking of the buffet as an attractive prospect to the clubs which, for us, were increasingly transforming into very boring and conservative spaces, where people had fun for the hundred-thousandth time to the idiotic sounds of the Red Hot Chili Peppers or Depeche Mode, sometimes Nick Cave. The passivity of repetition started to become unbearable, and so we slowly began staying at the buffet all evening, and would go straight home after, not into the city as before. Thereupon the buffet became our only underground nightlife.

I feel it is now my obligation to clarify to the reader as to why the cinema became so important to us. Naturally, the Nikšićko beer was not reason alone, the main reason was these older people we encountered, the informal group called Taksirat Party or the Party of Taksiratlis, the Party of the Wretched, who each and every night talked over beer, cards and dedikodi (gossip). Their stories were full of interesting anecdotes, their irony and lively jokes, shameless, and the endless talks were truly the lifeblood of the city, as I and my friend who went there recall it.

Now for a little anthropology. The Initiation. The Initiation into the Taksirat Party developed thus: At the beginning the Party would immediately familiarise the newcomer (in our case me, along with my friends) with their embodied knowledge of the city, so that the newcomer would become interested in details about this family she/he would come to belong to, how they function and where they live. If you were suited to their cartography of the city, they would call you kasabali and everything would be fine, you could join the gang. Kasabali meant, first of all, that you lived in the city, and second that your behaviour was befitting of a citizen, which meant not behaving as a qyli (a villager). Thereby, not to be stingy, to know how to have fun, to live, to love journeys, to know how to swim and how to eat well. Of course this reads as a petit-bourgeois philosophy, but in Prizren it can be something other, a provincial modernism. If any reader of the Pallanka Philosophy (provincial philosophy, in the words of Radomir Konstantinović) should come back with questions, the Party of the Wretched in the cinema would convince her/him of the veracity of that book, and would enable her/him to scientifically verify the anatomy of this provincial thought. According to the theory of the Party of the Wretched, it was not only important to live in the city, but to behave like a citizen, as I explained earlier. Hyshit lived in the city centre, but did not have a single quality befitting of citizenship by this rubric, and was therefore known as a villager. He was the least attractive in the whole Party. Boring like a villager. The rest of the members of the Party of the Wretched knew everything about the city. They knew with cadastral precision all of the (old) addresses and locations, all of the secrets held between families and an entire lexicon of untold stories. For us, most of these stories constituted a completely new experience of the city.

The ritual. The stories would begin like this: Almost every night Valon would announce the recent death announcements in the city to the buffet crowd. Those in the Party, would scrutinise it in detail and tell Valon when and where the funeral would commence, and he would later join it, all the way to the cemetery, and eventually get money for it. This was his favourite hijink. Whilst for the Party this was a cause for some analysis, naturally the analysis of life and identity of the deceased. Valon was the true spectacle of the Party from the cinema. A disabled borderliner, he would not speak anywhere but in the cinema. There, he communicated everything with Gjabir, who was the only one who could understand his language (Valon’s vocabulary was in its entirety different from the rest, for every single thing he had his separate system of description. Whereas Gjabir, apart from the three official languages of Prizren, also spoke Romani, plus the language of Valon!). Valon had different names for everyone, Mongol, Ybe, Pope… He used to call me Rambo. Gjabir told us that a professor of defectology, some psychologist, was really astonished when he saw Valon able to speak at the cinema, since from the time of school he had been mute.

Certainly there were other rituals and stories. The most intriguing were the stories told by the late Babo (or, The Motor). He had fought alongside the Italians against the Partisans, something that had soon become boring for him, but he had been able to learn Italian. The story of his trip to Malmo, Sweden, was interesting. He was constantly talking about the big bridge and the cabbage he had seen in a park there, and that he had been unable to take it with him (which made him feel somewhat badly). Babo was the head of the Party. The number one of the TNT band, as we called him. The whole Party was like Alan Ford. The other members of the Party were Gjabir (the manager), Haxhi Boza, Abdullah, Eran (the youngest member), Byka Tada and Hyshit. Of course, we were not members, but we had fun and we appreciated the ever present hospitality at the buffet, and the pleasure offered to us by this friendship, one now on the brink of extinction.

I would not like to seem like some romantic, with my nostalgia and my conservative fatalism; as the intention of this text is something altogether different and has a different politics at its heart. This is a story entirely opposed to the foolish and deleterious decision to demolish the cinema, a decision that will destroy the largest cultural manifestation in Prizren (that is, Dokufest) and which has already destroyed the Party. This is a decision that could only be made by people whom the Party would deem worthy of the label “qyli” or “those who know nothing of the City, but only think of money”.

Nota bene by Sezgin Boynik

The editors of the Lumbardhi blog recently asked me if they could reprint “Taksirat Partisi” as a document of the time, to which I agreed. It should be read as exactly that. Considering its prominent placement in the blog, I feel an obligation to add some further clarifications.

Soon after it was initially published, I disowned the text and completely distanced myself from its arguments. Though not from its spirit. This text was written hastily; if I remember correctly, in a bar in the midst of all the commotion of Dokufest. It is the product of a combination of politics, punk and libido. Indeed, I wrote it, but it was a distillation of collective confusions, contradictions, and despairs that we all felt at that time. It was, if I remember correctly, 2006 or 2007. We were all depressed by the fact that this community of older people, living completely outside of the grasps of consumerism and neoliberalism, would soon disappear. And with them the whole cinema, and any other place which was no longer generating money.

In the text, I wrongly accuse the “peasants” as being responsible for the plunder and pillage of such public institutions, and for the destruction of public space that occured after the arrival of the second millennium. This must be corrected; the privatisation, neoliberal plunder, wild urbanisation, and the illegal appropriations did not happen spontaneously, they were not the result of primitive kleptocracy, and it was not because of the insatiable greed of poor peasants. It was the outcome of well-organised parcelling, involving people with Master’s and Doctoral degrees, members of international construction boards, respectable and wealthy citizens.