Introduction: Partisan Spectacular Memory

Between 1945–1985, more than two-hundred films that dealt with topics about Partisans were produced in Yugoslavia[1]. Without any doubt, we can conclude that no other genre platform had such a strong imprint on the Yugoslav film production. We could also add that it was one of the marking features of the Yugoslav film abroad. In this text, I am interested in the most experimental and innovative period of the Yugoslav film production between the 1960s and 1970s. Yugoslav films that entered the international stage could roughly be perceived as produced for two international audiences: firstly, the independent auteur films which received different awards and mentions at film festivals (Cannes, Berlinale, Karlovy Vary etc.); secondly, the more mainstream films, such as Štiglic’s Ninth Circle (1960), or Bulajić’s major blockbuster Battle of Neretva (1969), nominated for the best foreign film at the Oscars.

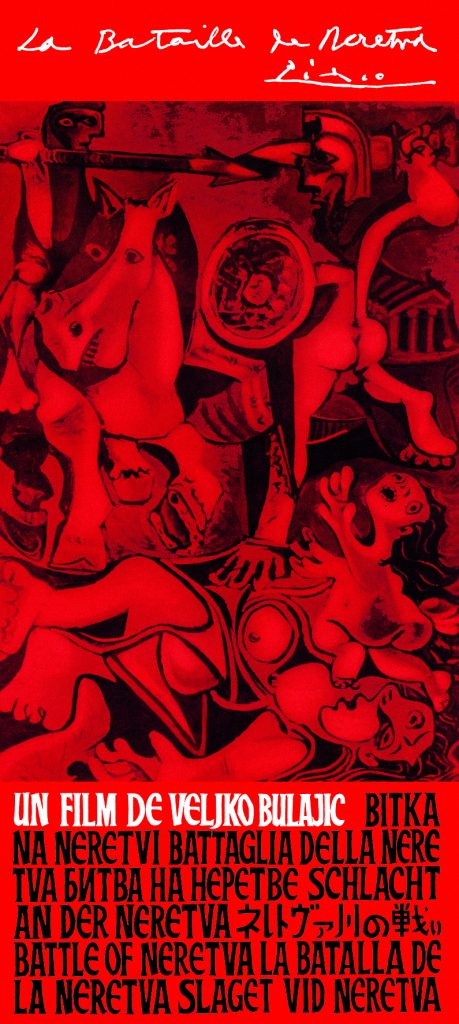

The Battle of Neretva was the most expensive production in the history of both the Yugoslav and the post Yugoslav film. Estimates range from five to ten million dollars at that time and it took almost two years to produce it. This film included sections of the Yugoslav People’s Army, which offered its manpower and infrastructure to the film crew’s disposal. The casting was composed of such international stars as Orson Welles, Yul Brynner, Franco Nero, Sylvia Koscina and Sergei Bondarchuk, while Pablo Picasso designed the poster for the English version of the film, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra composed the music. The film crew pursued a strong advertising campaign abroad, which made it an instant success. In Yugoslavia, more than 4.5 million spectators saw it in the first years of the release, while outside Yugoslavia around 350 million people.

The film plot focuses on the turning point for the partisan liberation movement, which fought for the survival of the general command under Tito and found themselves besieged by multiple fascist armies and collaborationist forces. It presents the epic overcoming of the siege as well as it portrays the heroism and sacrifices of the Partisans, including their humanity towards their wounded and typhoid-ridden comrades. The film lasts for almost three hours; it is accompanied by dramatic music and, seen in retrospect, it has started functioning as a part of the collective memory of the central battle of the liberation struggle. We might even argue that it became the most important visual and popular monument of the partisan struggle. People may have forgotten much from the textbooks; some may remember fragments from personal testimonials, or documentaries, but many from older and even some from the younger generations hold onto specific passages of this film: the legendary singing of the wounded that helps Partisan fighters push back against the Nazi annihilation, the resilience of Partisan fighters in the wake of being well-equipped and outnumbering the enemy. Such cultural artifacts played a vital role at least in achieving two tasks: firstly, these partisan films became Yugoslavia’s most celebrated film product on the global film market; and secondly, in Yugoslavia itself such films helped to mythologise the official memory on the Second World War and enable the actors and topics to enter into Yugoslav popular culture.

Any critical and independent filmmaker that wanted to make a film on the topic of the Partisans in the late 1960s or early 1970s had to pose a serious question on how to proceed further, since such hard to beat popular and spectacular images as those created by this film immediately emerged in front of the eyes. It is also true that most, if not all critical filmmakers, shared an open sympathy with the partisan struggle, but the central challenge was to find a way of affirming the partisan liberation while being able to articulate a non-partial view and differentiate itself aesthetically from the established film genre. Despite the difficulties of such a task, a number of critical film directors made some fascinating Partisan films that expressed their dissent either in terms of its aesthetics or by choosing a more complex narrative structure.[2] In this text I would like to present the visual and alternative memory strategies realised by Želimir Žilnik in his »Uprising in Jazak« (1973), according to which, the film remains as the most delicate bottom up reconstruction of partisanism and antifascism in (post)Yugoslavia.

Žilnik’s bottom up reconstruction, or on the “banality of goodness”

Želimir Žilnik is not famous for his films on the partisan struggle, however I would argue that he is the most important film author that has always taken sides and has inscribed in the very method of his film-making, a spirit and body of the partisan struggle. To make a film in a partisan way is a defining mark, differentia specifica of Žilnik’s now more than 5 decades long film activity. Uprising in Jazak (1973), as already his earlier works from the 1960s,[3] uses a method that holds onto traces of fictive and documentary »material« and testimony, which is sustained without the complete blending of one into another. Furthermore, the plot itself is based on a semi-prepared scenario, which demands both a degree of spontaneity in meeting and encountering the mostly amateur cast and a high level of focus on the part of the director, film crew and actors in dialectical responding to the situation of diegetic and real time and space. The trajectory of the plot and editing often gives the spectator the feeling that it could have developed in multiple ways.

But if the late 1960s were the most productive historical moments for cultural and political activities, where his pioneering and critical methodology came into existence, and where many film-directors experimented, then the early 1970s saw a conservative backlash and intensified political pressure on cultural workers. Despite this backlash, and being very conscious about potential consequences of persisting in producing such critical films, Žilnik goes on and produces one of the most exciting films, a true legacy of antifascist film methodology. Uprising in Jazak (1973) radically disturbs the dominant way in which Partisan struggle had been narrated, represented and finally remembered.

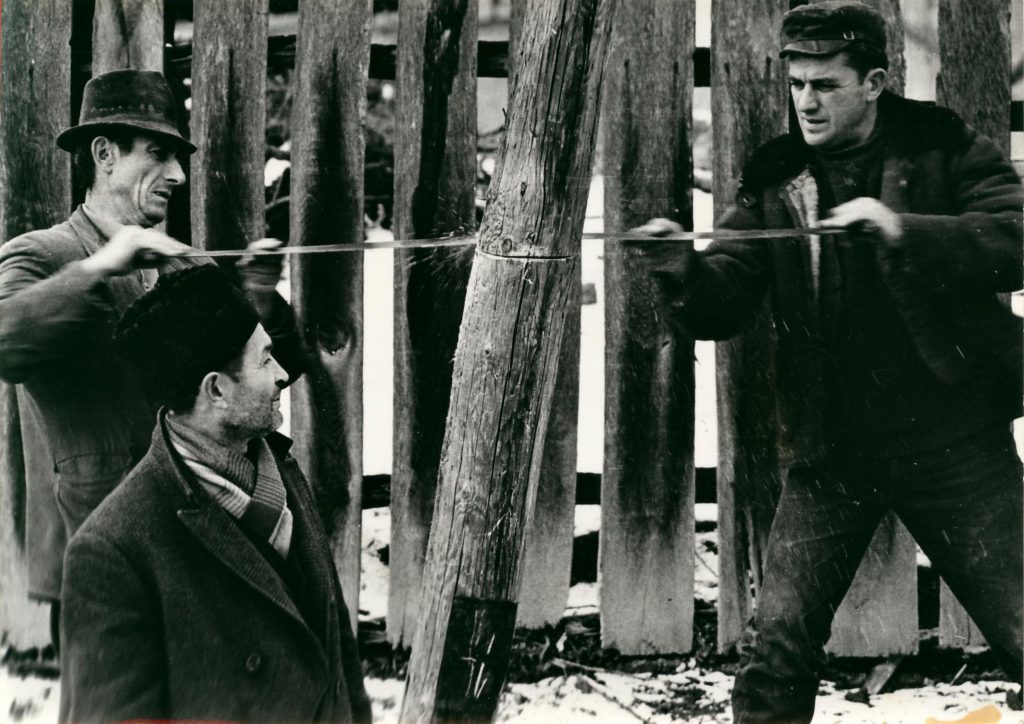

Uprising in Jazak departs from a shaky camera travel. The car with a film crew arrives to Jazak, almost 30 years after the end of WWII. They start interviewing people, including true witnesses and antifascists from the wartime period. A story of a local villager upon the arrival of the Nazis is accompanied by the visual passage of a shaky camera, the sound of moving tanks and shooting airplanes that attack and occupy the village. Žilnik makes the clear decision that he will not film and interview the national heroes, Partisan or communist leaders of yesterday or today, but the normal villagers, either supporters of the Partisans or those who eventually became Partisans. A large majority of these protagonists are neither politically ‘articulate,’ nor do they fit any heroic image of a Partisan fighter. What they do, however, is simply tell their stories in their own language. They speak of the arrival of the Nazis, then they show the camera the places where the torture took place and the techniques were used – and where the executions took place. But they also speak about their ways of resisting, how they performed the Partisan oath, where and how women were hiding and feeding Partisans, but also where they were hiding guns, food and transporting them to the Partisan fighters.

Žilnik thus openly counters the mainstream film representation that postured Partisan fighters as heroic figures that were seen as fighting and shooting the fascists. Such heroic partisans emblematized the figures of major sacrifice and were posited as a sort of »absolute good« that cannot and should not be questioned in aesthetical terms. I would suggest reading Žilnik’s move as a stark opposition to absolute heroes/ and the absolute good. Inverting Hannah Arendt’s term the »banality of evil,« (1977) Žilnik’s reconstruction of memory attributes to local villagers an aura and ethical attitude of »banality of good«. Since we all encounter the expression in an absolute term, the “radical evil” prevents us from thinking about the Nazi politics, the everyday dynamics of Nazism, and the question of collaboration – where the aforementioned is often explained as a sort of “banality of evil” and as people’s readiness to denounce Jews and political opponents of the Nazi authorities. If such a view at least attempts to understand why and how Nazism worked, then much less is written on the gestures of resistance, emancipation and liberation during the Second World War. This is why Žilnik’s memory strategy is of use for anyone interested in the deployment of the »banality of good«.

»Banality of good« is not to be understood as some sort of philanthropy on the part of those privileged enough to continue their normal living in the Nazi occupied Europe, nor does it refer to the noble gestures of rare individuals within the collaborationist apparatus (e.g. Schindler’s list). Rather, I argue that this rational choice to revolt could be part of a persisting ethics of the »banality of good«. How to understand the infrastructure of resistance in such dire circumstances of the occupied cities or villages, where any gesture and activity of resistance was immediately condemned to death? Žilnik’s film succeeds in displaying the antifascist community in Jazak in multiple gestures and activities that perform resistance. Žilnik’s response to heroic gestures entails the images and words of the resisting masses, of those from below that were allegedly not ‘dignified’ or ‘educated’ enough to remember or to be remembered, to narrate and represent the central event of the socialist Yugoslavia.

Some would commend Žilnik for conveying a more realistic and ‘truthful’ account of the Partisan past than the majority of Partisan films made at that time. This might as well be true, however I think that the more important observation is to focus on the manner of how the film was made. The film’s form consciously rejects any kind of aestheticization and this is not only the consequence of a lack of material means for the film’s shooting. Žilnik’s use of the »raw image« (see Levi 2007)[4] and the allegedly amateurish cutting that recurs in his work, are not a sign of laziness on the part of the editorial team, nor of poor technical equipment, but they rather express their conscious opposition to the aestheticization of the Partisan struggle. The raw film material, raw peasant life, the raw circumstances of war and the struggle for survival and liberation form a neorealist metonymic line of equivalence to Žilnik’s arrival and his take on Jazak. Furthermore, Žilnik openly rejects the dominant mode of representing the war as a spectacular form that focused solely on the Partisan battles, or on underground resistance in the urban centres. This is a film that shows how the vital infrastructure of the partisan liberation worked, and already realised a promise of a new world. Its primary political subjects were peasant masses.

Uprising in Jazak, as the name suggests, is a short film on the uprising of peasants. It explains why and how they struggled for the Partisan cause and not for the local collaborationists. Žilnik’s perspective in this film is directed from the standpoint of the ‘masses’ and could be seen as a reconstruction of testimonies from below, the film version of the »people’s history of resistance« (Gluckstein 2012). These people are not only subjects worthy of political attention and media archive, but they became subjects that remember for us, for the Yugoslav society and beyond. Žilnik also added an important layer in the format of a participatory survey, an addition in line with the Italian workerist tradition, which introduced collective participatory interviewing. This is masterfully inserted into the film dynamic, where the central events of village life and the resistance are narrated by the different voices of the participants. Their reconstruction is not simple and individualistic; during the filming these voices contradict each other and thus renegotiate the reconstruction of his/her/their stories. The impossibility to resist and create another alternative world is what I called partisan rupture (Kirn 2020), and the way how artworks worked on it, commemorated with the partisan remainder, is the difficult task undertaken by Žilnik here. The constant movement of the plot is dynamised by the switches in camera movement and the changes in focus to different storytellers and multiple voices. This reconstruction takes the shape of a collective bottom-up process of a memorial narrative and imaginary of Partisan village community-in-resistance. There is not a single voice, nor retrospective Communist Party history of the Partisan struggle, but a mosaic of all those who participated in it. Due to the scarce material, spectators have to imagine – with the help of sound and different film devices – locations and objects that are missing on the set. For example, once Žilnik’s film crew arrives in the village, the story brings us to 1941 and the arrival of the Nazi planes and tanks in the village. The film crew’s car is turned into a tank, and we see the images of the village and villagers from the moving car, which due to the conscious shaking of the camera and the editing of the sounds of moving tanks, imitate a tank passing through the village.

The collective and renegotiated memory of participants of the liberation struggle arrives to a clear political conclusion for their and our present: the epic battles and the victory of the Partisan struggle would not have been possible without broad popular support, especially from those in the countryside who sacrificed their lives, but also preserved their dignity and practiced mutual aid. In more historical sense, the countryside provided the struggle with the key infrastructure and the most vital means of reproduction for the entire Partisan movement. Žilnik’s film makes a significant shift from the conventional portrayal of civilians and farmers as passive victims of fascism, or civil war, and rather stages them as the central protagonists of antifascism. They become representatives of the everyday ‘banality of good,’ of those millions who supported and struggled all along the war. This memory strategy consists of a memorial re-enactment of people’ history with inventive and at first glance raw aesthetical means. The core of Žilnik’s method succeeds to put at display: how normal villagers became protagonists who took a clear side in the war; how 30 years later they become carriers and negotiators of public memory; and also how film itself politically and aesthetically practices how to make film in a partisan way. Uprising in Jazak re-enacts the uprising of the peasant masses, intensifies their echoes and visions, disturbing the dominant field of vision/narration in partisan films of that day.

Concluding: From partisan production to dissemination

The very last partisan gesture comes at the very end of the film production. In the moment when the film was edited and prepared for the first screenings, it was – as was customary – sent to the commission that controlled film production in Vojvodina.[5] This commission rejected it as unfit, to quote from Žilnik’s personal archive. It was designated as “an untruthful representation of the People’s Liberation Struggle […] while Žilnik offends the revolution by engaging a group of bumps who allegedly represent Partisans.” Neither Žilnik nor the protagonists took this judgement of the film lightly, as one can imagine. In yet another dramatic post-filmic unfolding of affairs, Žilnik, together with the most determined villagers-Partisans, entered the municipal office of the regional ministry of culture in Novi Sad. Having arrived without a formal invitation, the villagers display their 1941 Partisan memorial plaques, which confirm that they fought for the PLS from the very start of the war. They rush into the office of the then minister Djordje Popović whom they force to tear up the decision to ban the film. After a formal apology – “banning the film seems to have been a mistake” – Popović granted their demand and gave his permission for the film’s distribution. The film’s distribution can be seen as yet another continuation of Partisan politics by other means – a means that resisted the regional bureaucracy and its attack on the partisan art. This is how the Partisan memory of villagers, and Žilnik’s methods of production and dissemination, come full circle. The first projection took place in the village cinema a few days later and Žilnik recollects that the cinema was completely full and the showing concluded with long standing ovations. Uprising in Jazak was screened a few more times in the surrounding villages and in March 1973 at Belgrade’s short film festival, where it received several positive reviews and was warmly received by the audience. In April, the film went to the Oberhausen Film Festival and afterwards was withdrawn from distribution until 1984 when Žilnik finally received a copy of it.

All in all, Žilnik’s treatment of the partisan topic at the time, its permeated spectacular imagery and mythologising tendencies that helped reproduce the socialist authority, come forward as one of the few ways to successfully address the partisan rupture, the way to represent and commemorate from below, to cultivate revolutionary resources and genuine popular solidarity spanning beyond party lines and spectacular lenses of high budgeted spectacles. Such filmic retrieving of the fragments from the past can bring to us a much needed dosage of inspiration for struggles on the authoritarian horizons.

Bibliography

Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York, Penguin Books, 1977.

Badiou, Alain. Metapolitics. London, Verso, 2005.

Buden, Boris. Uvod u prošlost. Novi Sad: Kuda.org, 2013b.

Gluckstein, Donny. A People’s History of the Second World War. London, Pluto Press, 2012.

Kirn, Gal. Partisan Counter-Archive. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020.

Levi, Pavle. Disintegration in Frames: Aesthetics and Ideology in the Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema. Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2007.

Levi, Pavle. “Cine-Commune, or Filmmaking as Direct Socio-Political Intervention” (in Serbian), 2009. http://zilnikzelimir.net/sr/essay/kino-komuna-film-kao-prvostepena-drustveno-politicka-intervencija-1, Accessed 12 December 2019.

[1] This is a thoroughly revised and shortened section from the chapter 3 of my book Partisan Counter-Archive (De Gruyter: Berlin, 2020).

[2] Aleksandar Petrović’s Tri (Three, 1965), Štiglic’s Balada o Trobenti in Oblaku (Ballad of the Trumpet and the Cloud, 1961) Čap’s Trenutki Odločitve (Moment of Decision, 1955); Bauer’s Ne okreči se sine (My Son Don’t Turn Around, 1956). Secondly, there were films that had a more neorealist influence devoid of any heroism in the life of the Partisan struggle: Veljko Bulajić’s Kozara (1962), Mutapdžić’s Doktor Mladen (1975), Živojin Pavlović’s Zaseda (Ambush, 1969) and Hajka (1977). Finally, there were horror and surrealist films such as Puriša Djordjević’s Jutro (Morning, 1967) and Miodrag Popović’s Delije (1968); fourthly, there was a range of films that included a more complex depiction of the collaborationists, but also their authority from Lordan Žafranović’s famous film, Okupacija u 26 slika (Occupation in 26 Pictures, 1977), to Miodrag Popović’s Čovek iz hrastove šume (The Man from the Oak Forest, 1964), and also Vukotić’s Akcija stadion (one of the first Holocaust films from Yugoslavia, 1977).

[3] Early films such as Unemployed (1968), Black Film (1971), Uprising in Jazak (1973) and the feature film Early Works (1969), which all appeared as part of the production house Neoplanta in Novi Sad. There is a great documentation made by Žilnik and Kuda.org (Novi Sad) on Žilnik filmography (https://www.zilnikzelimir.net/), see also book from Buden (2013).

[4] Pavle Levi lucidly highlighted the political dimension present in this film method. Žilnik’s film characters most often “represent border examples […] between existing societies (within which they have no place) and possible, alternative, reorganized societies (within which – if these societies at some time were to be established – they would have clear and more stable identities). These characters are […] the material for a process that Etiènne Balibar described as the constituting of ‘the people,’ which is initially non-existent because of the exclusion of those who are considered unworthy of citizenship.” (2009, online)

[5] For details on the production process, see the personal correspondence with Želimir Žilnik (2018).

Gal Kirn has a PhD from the study program Intercultural studies of ideas at the University of Nova Gorica in Slovenia. He has since worked, among other places, at the Institute for Cultural Inquiry, Humboldt University in Berlin, GWZO in Leipzig and at TU Dresden. He has published on diverse topics from post-Fordism, and Yugoslav black wave cinema to Althusser and the critique of neoliberalism. His latest books deal with the topic of partisan struggle and socialist Yugoslavia, albeit from different angles. Partisan Ruptures was published by Pluto Press (2019) and deals with politico-economic investigation of the rise and demise of socialist Yugoslavia, while The Partisan Counter-Archive (De Gruyter, 2020) works on the triangulation of politics, art and memory on the case of partisan liberation struggle. He is currently Visiting Professor at Cultural History program at University of Nova Gorica.