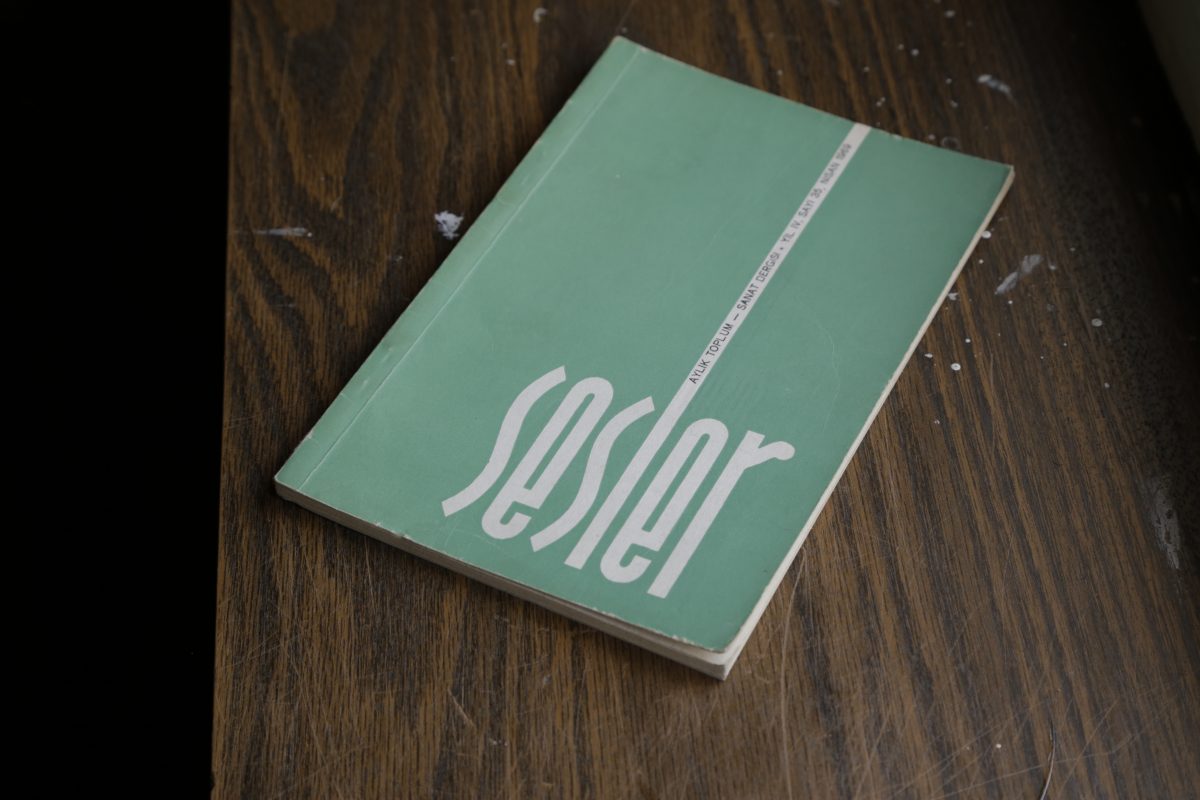

The first research post of the ‘Nation Formation’ project is based on a long and exhaustive article by Turkologist Ismail Eren (1923-1993) on the history of the Turkish print in Yugoslavia. Originally published as “Turska Štampa u Jugoslaviji” (1866-1966) it appeared for the first time in the Sarajevo-based journal “Prilozi za Orijentalnu Filologiju, issue 14-15”, in 1964. Later it appeared in Turkish in Sesler journal, based in Skopje (“Yugoslavya Topraklarında Türkçe Basın 1866-1966”, II: 9, 1966), and in an updated version in the late eighties in the same journal (“Yugoslavya’da Türkçe Basın 1866-1986”, Sesler No. 237). The latter version was also translated into French as “La Presse Turque en Yugoslavie” in 1992 (in N. Clayer, A. Popovic, Th. Zarcone, Presse Turque et Presse de Turquie, ISIS/IFEA, Istanbul/Paris).

Ismail Eren was a scholar from Macedonia who lived and worked in Istanbul. The text we present here was published in Bosnia in Serbo-Croatian. This trajectory alone supplies a foundation to the objective of our project; which is to study the formation of nationalism through concrete political institutions that were genuinely international. During socialist Yugoslavia, Eren contributed many scholarly articles on late Ottoman modernisation, urban life, and some highly regarded articles of research into folklore.

Eren’s article on the press in Yugoslavia uses the scholarly apparatus, a rigorous archival study and gives an overview of the journals, newspapers, and periodicals printed in the Turkish language in Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia. As well as imparting a picture of the richness and variety of printed materials in Turkish in Yugoslavia—which Eren laments as being less prolific and interesting than those in Bulgaria and Greece—the article depicts the context of this production very thoroughly. It makes us aware that these Turkish language periodicals published in Yugoslavia have to be understood by way of their social and political implications. The intensification of the publication of newspapers and magazines after the Second Constitutional Era (İkinci Meşrutiyet), which was established after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, is one of the topics the author deals with, pointing particularly to the modernising effect of the press, that was evidenced by the easing of legislation surrounding censorship and the liberalisation of the centralised control. That particular and very contradictory form of post-Empire modernisation, which in Yugoslavia lasted almost until the Second World War, presided over the publication of dozens of periodicals like Tarik, Muallim, and Misbah, written in Old Turkish (Arabic) script but using the Serbian-Bosnian language. This new mixture contributed to an unprecedented popularisation of printed material, as Eren writes, resulting in the reprint of some magazines’ issues from the back catalogue. Another outcome of this strange combination—Serbian literature written in Arabic script—was the emergence of the new style called arebica, or matufovica, which comes from matuf, in Arabic meaning old, but used colloquially to means upside-down, silly, strange, queer. (In recent years, in Bosnia, there have been attempts to reanimate this variant of writing the Bosnian language, as is the case with the comic book “Hadži Šefko i Hadži Mefko”, in 2005, backed by New Muslim Kids blog).

As Eren himself notes, there were some quite excessive examples of this turbulent history as well. For example, journals published by Ittihat ve Teraki with very bizarre militarised titles as Silah, Hançer, Bıçak, Bomba [Weapon, Dagger, Knife, Bomb], published in Skopje and Bitola, Top [Cannon] and Kurşun, Süngü, Kasatura [Bullet, Bayonet, Sword] in Skopje, all of which were opposition press and often in conflict with the ruling parties.

There are many other unusual outcomes of these politically driven prints. Perhaps the most obscure of all is Doğu ve Batı: Kültür, iktisat, sosyal ve siyası mecmuası [East and West: Culture, economy, society, and politics journal] published in Zagreb during the Second World War. As a publishing project, Doğu ve Batı is a pure historical anomaly. It is known as the first journal published in the Turkish language in Croatia, and the first Turkish language journal with Latin script published in Yugoslavia. There are eight numbers of this journal published between 1943 and 1944. It was an unsuccessful and aborted project of the Ustasha regime of the NDH [Nezavisna Država Hrvatska/The Independent State of Croatia, active in 1941-1945] government, which attempted to use this journal as the platform for cultural diplomacy, to attract the ruling bourgeoisie of Turkey to recognize the independence of fascist Croatia.

Eren’s article is also very good in presenting an image of the strong network of publishing activities within different Yugoslav and Balkan regions (vilayet), which also had a political dimension. Some of these periodicals were the most lasting, for example, Kosova (first issue published in 1877) was active for 35 years, and Manastir (first issue 1885) was active for 28 years. These intra-vilayet publishing activities required a multilingual platform, which was also how most of these publications were printed. As Eren convincingly demonstrates, the content and form of these publications were genuinely multi-lingual and trans-national; they were published in Serbian and Turkish (as Bosna, Prizren, Neretva), Albanian and Turkish (Üsküp/Shkupi in Skopje, Ittihad-i Milli/Bashkimi Kombit in Bitola). In the Balkans, there were even more diverse examples, such as newspaper Edirne, in every page including Turkish, Bulgarian, and Greek language texts, or Selanik, published between 1869 and 1871 which featured Hebrew language texts in addition to Turkish, Greek, and Bulgarian.

In the twenties, the press in Turkish developed into more explicit political platforms of different political parties; Sada-yi Millet [Voice of People] of conservative and right-wing Radical Party (1927-1929), Işık [Light] of liberal Democrat Party/Zajednica (1927-1928), and the short-lived, but certainly most progressive, Sosyalist Fecri [Socialist Dawn]which published only thirteen hard to find issues, in 1920. After the dictatorship established by King Alexander I, the king of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, in 1929, all parties and all press, including almost all press in the Turkish language, was banned in Yugoslavia. The next thing to be printed in Turkish, in that highly conservative and repressive atmosphere, was a newspaper published by The Islamic Community of Macedonia called Doğru Yol/Pravi Put [Right Path] in Turkish and Serbian. The following endeavour was also a newspaper of similar religious opportunist morality called Muslimanska Sloga [Muslim Consent] published in 1940, on the eve of the war.

Eren’s text finishes when the socialist period begins, which introduced the further expansion of publishing activities, especially of books, with even more diverse content. Eren briefly mentions that during the Second World War in 1944 in Skopje, the Turkish language newspaper of the National Front called Birlik [Unity] appears, which after the liberation was followed with other publications of Socijalistički Savez Radnog Naroda [The Socialist Alliance of Working People of Yugoslavia], Pioner Gazetesi [Pioneer Newspaper], Yeni Kadın [New Woman], Tomurcuk [Sprout], Sevinç [Joy], and Sesler [Voices].

The new life of the Turkish language in the socialist print in Yugoslavia arrives with these seeds, which will be the subject of the rest of the posts in this blog.